A company invests six months of development time and two million dollars building a shiny new customer portal. The development team delivers precisely what the requirements document specified. Yet within weeks of launch, users abandon the system in frustration, citing confusion and counterintuitiveness. The project was completed on time and on budget, but it failed spectacularly. What went wrong?

This situation plays out more often than you might think, and it perfectly illustrates why business analysis has become such a critical discipline in modern organizations. At its heart, business analysis is about bridging that dangerous gap between what stakeholders think they want and what will actually solve their problems. It goes deeper than surface requests to uncover real needs.

If you have ever wondered what business analysis really means beyond the buzzwords, you are not alone. The term is mentioned in meetings and featured in job descriptions, yet its true scope often remains unclear. This guide will walk you through the essentials, showing you how the field works and why it matters.

The Evolution of Business Analysis: Understanding the Context

To truly understand what business analysis means today, you need to see how dramatically the profession has transformed over the past fifteen years. The changes reflect broader shifts in technology, methodology, and organizational thinking.

2010 to 2015: The Documentation Era

During this period, business analysts primarily functioned as requirement documenters and intermediaries between business units and IT departments. The work followed predictable patterns:

- Waterfall methodology dominated, with everything planned in detail upfront

- Analysts spent weeks crafting comprehensive requirement specification documents

- The role centered on translating business language into technical specifications

- Microsoft Office tools formed the primary toolkit

- Analysis often happened in isolation rather than in collaboration

- Success meant completing documentation, regardless of outcome

Business analysts worked in structured environments where changing requirements required formal approval processes and extensive document updates. The focus was more on process compliance than actual value delivery.

2015 to 2022: The Agile Transformation

Everything shifted as organizations embraced agile methodologies and digital transformation accelerated. The changes came fast and fundamentally altered the BA role. User stories and acceptance criteria replaced lengthy requirement documents. Business analysts stopped being solo documenters and became active facilitators in cross-functional teams.

Product ownership emerged as a natural extension of business analysis work. Data analytics capabilities became increasingly important as organizations realized that decisions required data support. Cloud adoption changed how solutions got designed and deployed. This era saw business analysts working alongside developers during daily standups, iterating on solutions through continuous feedback loops.

2023 to Present: The AI and Strategic Era

We are living through the most significant transformation yet. Artificial intelligence and machine learning have become analysis tools themselves, not just subjects of analysis. Generative AI now assists with everything from documentation to data pattern recognition to insight generation.

Real-time analytics enable faster, better-informed decision-making. Sustainability and ESG requirements now factor into every analysis, not as afterthoughts but as core considerations. Remote collaboration tools have fundamentally changed how analysts work with distributed teams. Perhaps most importantly, business analysts now serve as strategic advisors at the leadership table rather than merely supporting project execution.

The profession evolved from documentation specialist to agile facilitator to strategic partner. That journey continues.

What is Business Analysis? The Core Definition

At its simplest, business analysis is the practice of helping organizations figure out what they need, understand why they need it, and determine how to make it happen.

But that basic definition barely scratches the surface of what the discipline actually involves in practice.

Breaking Down the Definition

Think of a business analyst as part detective, part architect, part psychologist. They investigate organizational problems like a detective uncovering clues. They design solutions like an architect creating blueprints. They navigate human dynamics like a psychologist, understanding motivations and resistance. The work weaves together several interconnected activities that are equally important.

a) Identifying business problems and opportunities always comes first, and it requires looking past surface symptoms to understand root causes. When sales numbers drop, the obvious answer might be poor marketing or product quality issues. But the real problem may be a confusing checkout process, inefficient fulfillment, or customer service that drives customers away. Getting this diagnosis right makes everything else possible.

b) Understanding stakeholder needs goes way beyond simply asking people what they want. Here is the thing: stakeholders almost always describe solutions rather than problems. Someone says they need a mobile app when what they really need is field access to customer data. They request automated reporting, even though the actual issue is that current reports contain useless metrics. A skilled business analyst digs past those solution requests to uncover the underlying needs driving them.

c) Recommending solutions that deliver genuine value means evaluating options with clear eyes and honest assessment. The best solution balances multiple factors, including cost, technical feasibility, implementation risk, and expected benefit. Sometimes, after thorough analysis, the correct answer is to do nothing at all because the cost outweighs any realistic benefit.

d) Facilitating organizational change acknowledges a truth that many technical projects ignore: solutions only work if people actually adopt them. The most brilliant system design fails if users reject it or work around it. Business analysts help organizations navigate the human side of change, addressing concerns, managing resistance, and building buy-in. Technical implementation represents only half the battle.

The Official Definition

The International Institute of Business Analysis (IIBA), which sets global standards for the profession, defines business analysis as the practice of enabling change in an organizational context by defining needs and recommending solutions that deliver value to stakeholders.

That formal definition emphasizes three elements that are equally important: enabling change, accurately defining needs, and delivering measurable value. Miss any one of those three, and the analysis falls short.

Where Business Analysis Happens

The discipline extends far beyond IT projects, though technology initiatives are where many people first encounter business analysis work. The principles and practices apply across every type of organizational challenge:

- Strategic planning sessions that shape organizational direction

- Process improvement initiatives in any department, from HR to manufacturing

- Product development programs are creating new offerings

- Digital transformation efforts are modernizing operations

- Merger and acquisition integration brings organizations together

- Regulatory compliance programs meeting new requirements

- Risk management initiatives protecting organizational assets

Anywhere an organization needs to understand a complex problem and implement an effective solution, business analysis adds value. The core principles stay consistent even as contexts change dramatically. Whether working with executive leadership on a three-year strategy or with frontline teams on workflow improvements, business analysts bridge the gap between the current reality and the desired future state.

Core Business Analysis Techniques

Different problems call for different approaches, which is why business analysts develop proficiency across various analytical techniques. The real skill lies not just in knowing these techniques but in recognizing which one fits each situation and how to combine them effectively.

Technique #1: SWOT Analysis

SWOT examines four key dimensions:

- Strengths

- Weaknesses

- Opportunities

- Threats

This framework works particularly well during strategic planning or when evaluating major initiatives because it forces systematic consideration of both internal capabilities and external factors.

Consider an e-commerce company analyzing international expansion:

- Their SWOT might reveal strong brand recognition and robust technical infrastructure as strengths.

- Limited international logistics experience and regulatory knowledge appear as weaknesses.

- Growing demand in Southeast Asian markets represents a clear opportunity.

- Established competitors already operating in target regions pose a significant threat.

This structured view helps leadership make informed decisions about timing, resource allocation, and strategic approach.

Technique #2: Requirements Elicitation

Gathering requirements involves far more than sending out a survey or holding a single meeting. Practical requirements gathering combines multiple complementary techniques, including stakeholder interviews, facilitated workshops, direct observation, and document analysis. Each method reveals different insights.

When a hospital wants to improve patient check-in, for instance, an analyst might shadow front desk staff to observe the actual workflow rather than an assumed one. They interview nurses to determine what information is needed upon patient arrival and facilitate workshops with patients themselves to understand frustrations and expectations. Then they review existing forms, policies, and error logs. Together, these varied perspectives paint a complete picture that no single method could provide.

Technique #3: Business Process Modeling

Visual representations of how work flows through an organization make complex processes understandable to diverse audiences. Process modeling uses standardized diagrams to show sequential steps, decision points, handoffs between departments, and bottlenecks where work gets stuck.

For example, mapping an insurance claim approval process might reveal that applications sit idle for days between departments, not because anyone is slow, but because no straightforward handoff procedure exists. The visual format makes such problems obvious in ways that text descriptions never could.

Technique #4: User Stories and Use Cases

Popular in agile environments, user stories capture requirements from the perspective of the person who will use the solution. They follow a simple template:

As a [type of user], I want [specific goal] so that [clear benefit].

For a banking app, this might read: As a mobile banking customer, I want to deposit checks using my phone camera so that I can skip trips to the branch.

This format keeps teams focused on user needs and outcomes rather than getting lost in technical specifications. Use cases provide more detailed scenario documentation for complex interactions.

Technique #5: Gap Analysis

Understanding the difference between the current state and the desired future state helps teams prioritize improvements and allocate resources effectively. Gap analysis identifies not only what needs to change but also why and how much effort it will take to close each gap.

A manufacturing company might document that current production takes 10 hours per unit with a 15% defect rate, while their target is 6 hours per unit with a 5% defect rate. Analyzing these gaps systematically reveals whether solutions require new equipment, better training, process redesign, or some combination of all three.

Technique #6: MoSCoW Prioritization

When resources are limited, and everything seems important, teams need a framework for making tough choices. MoSCoW categorizes requirements into four buckets:

- Must have

- Should have

- Could have,

- Will not have

During a website redesign, this might mean classifying mobile responsiveness as “Must have” because users increasingly access the site on phones. Improved search functionality becomes “should have” because it adds value, but the site works without it. Social media integration falls into “Could have” as a nice addition when time permits. A customer forum gets tagged “Will not have” for the initial launch to keep the scope manageable.

Technique #7: Stakeholder Analysis

Every project involves people with different interests, varying levels of influence, and sometimes competing concerns. Stakeholder analysis maps these complex relationships to guide communication strategies and change management approaches. An analyst might plot stakeholders on a Power and Interest grid that shows their power to affect the project and their level of interest in its outcomes:

- High power, high interest

- High power, low interest

- Low power, high interest

- Low power, low interest

Putting the above classification into perspective:

- The CEO has high power but medium interest, so provide regular executive summaries without overwhelming detail.

- Department managers have medium power and high interest; involve them deeply in planning and decision-making.

- End users have low power but high interest, so keep them well informed about progress and solicit their feedback on prototypes.

- Security and compliance teams have high power but low interest until their domain gets affected, so engage them early on relevant topics.

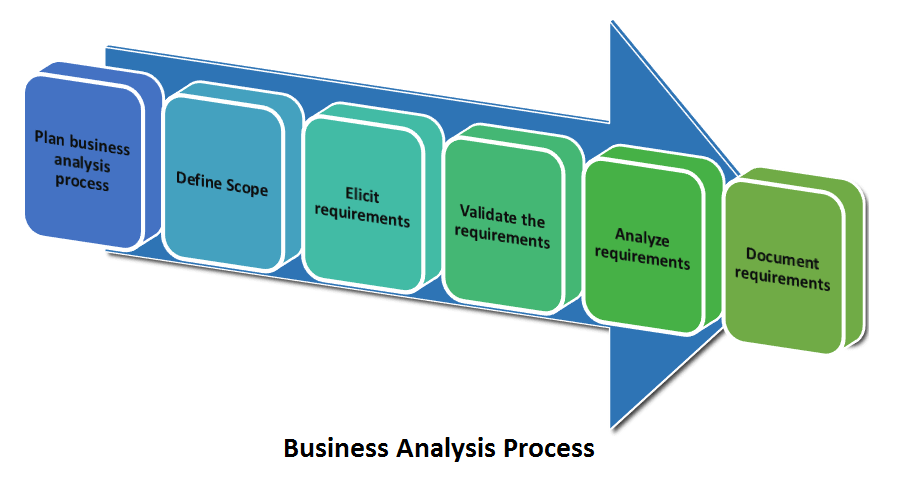

The Business Analysis Process: How It Actually Works

Understanding individual techniques provides valuable tools, but seeing how they fit together into a complete process reveals the true value of business analysis. Let me walk you through a realistic scenario from start to finish so you can see how this actually plays out in practice.

Phase 1: Identify Business Needs

A mid-sized retail company observes a 20% decline in online sales over three months. The initial response from leadership is predictable: they assume the website design has become outdated and needs a refresh. Before accepting that diagnosis, a business requirements analyst digs deeper to understand what is really happening.

The sales team reports that customers frequently call to check order status, suggesting communication gaps in the process. Marketing shares data showing their recent campaigns successfully drove traffic to the site, but conversion rates dropped significantly. The IT department noted increased cart abandonment rates but attributed them to normal seasonal variation. Finance points to the revenue impact but lacks visibility into the root causes.

Digging into the analytics data reveals a clear pattern: 68% of customers abandon their shopping carts at checkout. The problem is not the website’s overall design, but a defect in the checkout flow. This discovery completely reframes the project. Instead of a costly, time-consuming redesign, the focus narrows to fixing the root cause of checkout abandonment.

Phase 2: Gather and Analyze Requirements

Now the analyst needs detailed information about what works and what does not in the current checkout process. Multiple requirements elicitation techniques are used, each revealing different pieces of the puzzle.

Workshop sessions with the customer service team surface the top complaints they hear repeatedly: too many steps in checkout, forced account creation, confusing error messages, and limited payment options. The UX designer contributes heat map data showing exactly where users click away. Session recordings reveal patterns of behavior that explain the numbers.

Direct customer interviews provide invaluable context that data alone cannot capture. One customer explains: “I had everything picked out and ready to buy, but creating an account with all those password requirements and filling out endless forms took so long that I just went to Amazon instead. They let me check out as a guest in about thirty seconds.” Another customer reports having to enter the same shipping address three times across different screens within the same checkout flow.

Technical analysis reveals the full scope of the problem. The current checkout process spans seven distinct steps. It takes an average of 8 minutes from cart to confirmation. It requires users to complete 24 form fields, many of which are redundant. Industry benchmarks for e-commerce suggest a maximum of three steps and a total time under three minutes, with most successful sites achieving checkout in under two minutes.

The business analyst documents specific requirements using MoSCoW prioritization to create a shared understanding across the team:

Must have requirements: Reduce checkout from seven steps to a maximum of three. Add a guest checkout option to make account creation optional. Ensure transactions are processed in under three seconds. Fully support mobile devices with a thumb-friendly interface.

Should have requirements: Save cart contents for thirty days so customers can return later. Support multiple payment methods, including popular digital wallets. Add address autocomplete functionality to reduce typing.

Could have requirements: Offer one-click purchase for returning customers with saved preferences. Integrate with the existing loyalty program for automatic point tracking.

Will not have this release: Cryptocurrency payment options remain too complex for initial launch. International shipping gets deferred to phase two.

Non-functional requirements matter just as much as features. The system must handle ten thousand concurrent users during peak shopping periods. It needs to maintain 99.9% uptime. Security must comply with PCI-DSS standards for payment processing. These technical requirements ensure the solution works reliably at scale.

Phase 3: Define Solutions and Implement

With precise requirements in hand, the analyst presents three potential solutions, each with an honest cost-benefit analysis. Option A involves completely rebuilding the checkout system from scratch. The cost is $250,000, the timeline is 6 months, and the risk is high because it would disrupt everything at once. Option B takes a phased approach to improvement, upgrading the existing system incrementally. Cost drops to $120,000; initial improvements launch in three months; and risk is medium, as changes are validated before full rollout. Option C integrates a third-party checkout solution. Cost is lowest at $80,000, plus $2,000 in monthly licensing fees. Implementation takes just six weeks, and risk stays low because the solution is proven. However, it creates vendor dependency and ongoing costs.

After evaluating trade-offs, the team chooses Option B. It balances cost, risk, and timeline while allowing validation at each phase. If early improvements boost conversion, they can accelerate remaining phases. If something does not work as expected, they can adjust course before investing everything.

During implementation, the analyst works closely with multiple teams. UX designers create wireframes for the streamlined three-step checkout. Developers define API requirements for payment processing. The security team ensures encryption standards for customer data. With marketing, they plan to communicate to customers about the improved experience. This collaboration ensures technical solutions and business needs stay aligned throughout development.

Phase 4: Evaluate Results

Three months after the first phase launches, the numbers tell a clear story. Cart abandonment dropped from 68% to 31%. Average checkout completion time decreased from eight minutes to two and a half minutes. Customer satisfaction scores increased by forty percent. Support calls specifically about checkout problems decreased by sixty percent.

The financial impact validates the investment. Online sales increased by 45% in the first quarter following implementation. Mobile conversion rates improved by seventy-eight percent once the thumb-friendly interface went live. A $120,000 investment generated $380,000 in additional revenue in the first quarter alone, delivering a 217% return on investment. That does not even account for reduced support costs and improved customer lifetime value from a better experience.

Business Analysis Methodologies: Different Approaches

No single methodology works in every situation, which is why mature organizations maintain flexibility in their approach to business analysis.

Agile Business Analysis uses iterative, incremental approaches. Work happens in short sprints with continuous stakeholder collaboration and frequent delivery of working solutions. User stories capture requirements in an accessible language. Retrospectives drive continuous improvement. This methodology shines in software development projects where requirements evolve as teams learn.

Waterfall methodology follows a sequential set of phases, with comprehensive documentation at each stage. Requirements get fully defined upfront before design begins. Testing happens after development completes. This structured approach works well in regulated industries such as banking and healthcare, where compliance is critical, and requirements remain relatively stable.

Lean Six Sigma focuses relentlessly on efficiency and waste reduction through data-driven analysis. The DMAIC framework (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) provides a structured approach. Statistical tools identify root causes. This methodology excels in manufacturing and operations where measurable process improvement is the goal.

Design Thinking emphasizes human-centered problem solving. It starts with deep empathy for users, generates many solution ideas through brainstorming, builds quick prototypes for testing, and iterates based on feedback. This approach works beautifully for customer experience initiatives and innovation projects where the solution space is wide open.

Most successful organizations today use hybrid approaches that combine elements of multiple methodologies, tailored to project context, organizational culture, stakeholder preferences, and regulatory requirements. The key is to choose consciously rather than defaulting to a single way of working.

Business Analysis Tools and Technologies

Modern business analysts rely on a diverse toolkit of software and platforms to document their work, analyze data, and collaborate effectively with distributed teams.

Documentation and Modeling Tools

Microsoft Visio, Draw.io, and Lucidchart help create visual process flow diagrams, entity relationship diagrams, and wireframes that communicate complex information at a glance. Confluence and SharePoint serve as centralized repositories for requirements documentation and knowledge management, ensuring everyone works from the same information. JIRA tracks user stories, manages sprint backlogs, and provides visibility into agile project progress for the entire team.

Data Analysis Tools

Excel and Power BI remain workhorses for data manipulation, statistical analysis, and creating visualizations that make patterns visible. SQL enables direct database querying to extract and analyze data without waiting for IT to provision. Tableau creates sophisticated, interactive dashboards that allow stakeholders to explore data and uncover insights.

Collaboration Platforms

Slack and Microsoft Teams facilitate real-time communication across distributed teams, replacing endless email chains with threaded conversations. Miro and Mural provide digital whiteboarding capabilities that make remote workshops nearly as effective as in-person sessions. These tools became essential during the pandemic and remain valuable as hybrid work continues.

Emerging Technologies

AI-powered analytics platforms are transforming how quickly analysts can process information and generate insights. ChatGPT and similar tools help draft requirements documents, analyze qualitative feedback at scale, and even suggest questions to ask stakeholders. Low-code and no-code platforms enable rapid prototyping, allowing analysts to demonstrate rather than just describe proposed solutions. Cloud platforms provide scalable infrastructure and allow real-time collaboration that would have been impossible just a few years ago.

Choosing the Right Tools

Tool selection depends on organizational standards to ensure compatibility, team familiarity, which affects adoption and productivity, integration capabilities with existing systems, budget constraints that limit options, and scalability needs as projects grow. The most effective analysts master foundational tools that work everywhere while staying current with emerging technologies that can provide a competitive advantage.

Conclusion: Why Business Analysis Matters

Business analysis transforms organizational challenges into opportunities through structured problem solving, genuine stakeholder collaboration, and thoughtful solution design. It bridges the persistent gap between business needs and technical solutions, ensuring that projects deliver measurable value rather than just completed tasks.

Organizations with mature business analysis practices consistently experience higher project success rates, better requirement accuracy that reduces expensive rework, improved stakeholder satisfaction throughout initiatives, faster time-to-value from completed projects, and reduced waste from building the wrong things.

The discipline has evolved dramatically from pure documentation to strategic partnership. Today’s business analysts serve as transformation leaders who shape organizational direction rather than just supporting project execution. As systems analysts focus on technical architecture and infrastructure, business analysts ensure solutions actually solve business problems. The field offers tremendous opportunities for people who enjoy analytical thinking, problem-solving, and making tangible organizational impact.

Whether you are exploring what business analysts do day-to-day, considering the many benefits of becoming a business analyst, or trying to understand how specialized roles differ, business analysis provides a foundation that applies across industries and contexts. As technology advances and business complexity grows, skilled business analysts who can navigate ambiguity, facilitate collaboration, and drive results remain essential to organizational success.